Systems and rules are for the fools, and it needs power of imagination to fool the system.

Piyush Pandey’s writing is like an onion with endless layers that seamlessly unravel clues in simplicity of everyday living. Such is the beauty of his writing that it takes the reader along, making he or she traverse the distance as if it has been one’s own.

The only difference being that we allow memories of encounters with the likes of cobblers and carpenters to fade away. He, instead, retrieves them at short notice to seek imaginative insights and fresh perspectives. He does it with ease and ability because he hasn’t allowed the ‘child’ in him to die, which has made him an extraordinary ‘man’, albeit an ad-man.

Pandeymonium is loaded with intriguing insights and creative ideas, offering subtle but profound reflections on how indeed professionals must guide their lives. Aren’t a vast majority trapped in preconceived notions and unknown fears to break new ground, lamenting instead that the system sucks their creative energies? Don’t be scared of systems and processes, echoes Piyush, there are ways to fool them. This reminds me of veteran journalist and distinguished editor Pran Chopra who often used to say “Follow the rules to break the rules”. Systems and rules are for the fools, and it needs power of imagination to fool the system.

Primarily written for advertising professionals, as the title page suggests, the straight-from-the-heart narrative of experiences can capture the attention of any avid reader. Quick to read and easy to grasp, it is a book about letting big ideas fly on the wings of imagination. It is a book on generating and shaping convincing ideas. It is a book about building relationships with those with whom you have nothing in common. Finally, it is a book about going underwater and marveling at the iceberg that you don’t get to see otherwise.

Each of his award-winning creations has an interesting story lurking behind. Be it the series of Fevicol commercials or numerous Vodafone Zoozoos, Piyush has applied his cricketing skills to step out of the crease to score the maximum. For stepping out, one needs to be confident about the idea. Quite often, a lot of professionals are insecure about their idea. The less you share the idea, the less the possibility for a good idea to become great. The caveat, however, is to use those sounding boards with whom you can share and confide. The genesis of a big work comprises a big heart, big vision, big belief and big faith.

Pandeymonium brings together the power of ideas and perceptions to win clients and the audiences. Having demonstrated it through his work, the author wonders why should anyone feel deprived when one’s own learning has given some important weapons — the power of imagination, the power of your pen, and the power to communicate effectively. Important as it is, to be sure about one’s idea is not to worry about accusations and suspicions.

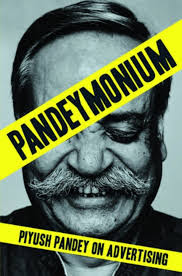

Born into a family with eight siblings, Piyush spent his formative years in Jaipur before moving out to do his master’s at St Stephen’s College, Delhi. A passionate cricketer, having played in the Ranji Trophy, he integrated all his experiences of life in carving out a prestigious position in the ad world. Sporting a prominent Walrus mustache, his weary smile on the cover page reflects a face of creative conviction and satisfaction.

Piyush’s autobiographical journey is all about small experiences, interactions and encounters in life. Each experience is worth its weight in gold, provided one knows how to draw insights from it. The take home message from the book is that we each have a story to tell, but the story can only be great if the story is humane in nature and can touch hearts.

Pandeymonium

by Piyush Pandey

Penguin, New Delhi

Extent 244, Price Rs 799

This review was first published in Deccan Herald on December 20, 2015.

Piyush Pandey’s writing is like an onion with endless layers that seamlessly unravel clues in simplicity of everyday living. Such is the beauty of his writing that it takes the reader along, making he or she traverse the distance as if it has been one’s own.

The only difference being that we allow memories of encounters with the likes of cobblers and carpenters to fade away. He, instead, retrieves them at short notice to seek imaginative insights and fresh perspectives. He does it with ease and ability because he hasn’t allowed the ‘child’ in him to die, which has made him an extraordinary ‘man’, albeit an ad-man.

Pandeymonium is loaded with intriguing insights and creative ideas, offering subtle but profound reflections on how indeed professionals must guide their lives. Aren’t a vast majority trapped in preconceived notions and unknown fears to break new ground, lamenting instead that the system sucks their creative energies? Don’t be scared of systems and processes, echoes Piyush, there are ways to fool them. This reminds me of veteran journalist and distinguished editor Pran Chopra who often used to say “Follow the rules to break the rules”. Systems and rules are for the fools, and it needs power of imagination to fool the system.

Primarily written for advertising professionals, as the title page suggests, the straight-from-the-heart narrative of experiences can capture the attention of any avid reader. Quick to read and easy to grasp, it is a book about letting big ideas fly on the wings of imagination. It is a book on generating and shaping convincing ideas. It is a book about building relationships with those with whom you have nothing in common. Finally, it is a book about going underwater and marveling at the iceberg that you don’t get to see otherwise.

Each of his award-winning creations has an interesting story lurking behind. Be it the series of Fevicol commercials or numerous Vodafone Zoozoos, Piyush has applied his cricketing skills to step out of the crease to score the maximum. For stepping out, one needs to be confident about the idea. Quite often, a lot of professionals are insecure about their idea. The less you share the idea, the less the possibility for a good idea to become great. The caveat, however, is to use those sounding boards with whom you can share and confide. The genesis of a big work comprises a big heart, big vision, big belief and big faith.

Pandeymonium brings together the power of ideas and perceptions to win clients and the audiences. Having demonstrated it through his work, the author wonders why should anyone feel deprived when one’s own learning has given some important weapons — the power of imagination, the power of your pen, and the power to communicate effectively. Important as it is, to be sure about one’s idea is not to worry about accusations and suspicions.

Born into a family with eight siblings, Piyush spent his formative years in Jaipur before moving out to do his master’s at St Stephen’s College, Delhi. A passionate cricketer, having played in the Ranji Trophy, he integrated all his experiences of life in carving out a prestigious position in the ad world. Sporting a prominent Walrus mustache, his weary smile on the cover page reflects a face of creative conviction and satisfaction.

Piyush’s autobiographical journey is all about small experiences, interactions and encounters in life. Each experience is worth its weight in gold, provided one knows how to draw insights from it. The take home message from the book is that we each have a story to tell, but the story can only be great if the story is humane in nature and can touch hearts.

Pandeymonium

by Piyush Pandey

Penguin, New Delhi

Extent 244, Price Rs 799

This review was first published in Deccan Herald on December 20, 2015.